The consequences of using State over Cache and its impact on data consistency.

All of the concepts presented here are applicable to any other technology, even I have been using it with plain html and also with desktop apps in rust. All code examples are in a “pseudo javascript code” style, don’t focus literally on the code, but on the design and architecture presented with the following examples.

The simple problem

It all begins with a straightforward challenge: you have a frontend, any frontend, and you require interaction with an internal or external API. For the sake of this post, let’s assume you’re developing a web application that interacts with a REST API, with or without caching support.

In a perfect scenario where you have a fully documented API and you know all possibilities of data mutation, you could store and handle it in a more hardcoded and smart way, but lets be fair, software has a lot of moving parts, you can never be sure of anything. Said that, client code generation, complex caching mechanisms and other things that a schematized API can provide are not always available. Still, most of the time you have to deal with writing requests functions manually, and this is where everything goes down the road.

After some minutes coding, you will end up with something (hopefully more complex) like this:

function getUser(name) {

return fetch('https://api.com/user/' + name);

}So, you call getUser() whenever you need to get the data for a specific user. But what about the two components in two other different component hierarchy trees in the screen who need to show the same data from the same user? Will you call getUser() again and again to have multiple network travels? No.

We brought another new simple problem

Well, a simple problem must have a simple solution, right? And here is where you start using state to solve your simple-not-anymore problem.

// This variable represents some library that shares data in a global perspective,

// like Redux for the React ecosystem.

const state = new Map();

function getUser(name) {

// checks if the state has the user

if (state.has(name)) {

return state.get(name);

}

// fetches and saves the response

const user = fetch('https://api.com/user/' + name);

state.set(name, user);

return user;

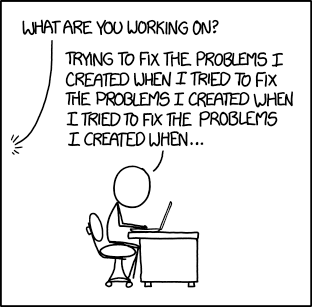

}And the 1739 XKCD comic comes to a hard reality once again:

Imagine if another piece of code, whether on the same machine or in a parallel universe, alters the state that you are currently displaying. In such a scenario, your simple utilization of state turns into a nightmarish puzzle to debug and resolve, as it remains frozen in time.

One potential approach is to implement your own cache revalidation mechanism within your state control code. However, the harsh reality is that creating a flawless cache mechanism is extremely challenging (and I genuinely mean it, as I happen to be the maintainer of Axios Cache Interceptor). Most of the time, people resort to freezing the cache without incorporating any form of revalidation. Alternatively, for time-critical data, caching may not be utilized at all.

Possible cache implementations

The primary objective of this post is to guide you in avoiding the storage of any data in a state and instead directly interacting with your API using a cached API client. However, before we dive into that, let’s explore some potential cache implementations that you can consider for your application. Chances are, you may have already come across some of these approaches.

Define a specific TTL (time to live) for each request. This means that after a certain period of time, the data will be refreshed with the latest response from the remote server. This approach is widely used as it strikes a balance between data consistency and minimizing network requests.

Listen to real-time event sources, such as websockets, to receive updates for specific data. Only the mutated portion of the data will be transmitted to the client, ensuring minimal network connections. However, this approach demands significant resources, effort, and ongoing maintenance. It may not be the preferred solution in many cases, as it increases network usage and enforces a higher level of data consistency that may not always be necessary.

Implement caching mechanisms such as ETag and/or Cache-Control for HTTP connections (or any other cache specifications relevant to your specific protocol). This implementation will likely require integration with a library that handles the various specific behaviors for different use cases within your State Management code alongside your frontend, or to pray that your only clients happens to be a web browser.

And many other solutions that don’t need to be listed here…

The Cache “Statization” Phenomenon

The utilization of State Management libraries has gained significant popularity, and as a result, more and more individuals are attempting to replicate cache behaviors by manually implementing them within their State Management code. This trend can be referred to as Cache “Statization”.

Now, you might wonder, why bother “statizing” the cache when you can simply use an actual cache? The truth is, there is no valid reason to do so. Just because global state management is widely employed in codebases doesn’t imply that it addresses all issues comprehensively.

Kent C. Dodds has a great tweet about it:

UI state should be separate from the server cache (often called “state” as well), and when you do that, you don’t need anything more than React for State Management.- Kent C. Dodds, Nov 24, 2019.

This concept prompts a valuable discussion about segregating the data in your application into two distinct layers: the UI data (state) and the API data (cache).

Considering that combining cache with our state can lead to complications, and managing API data is significantly simpler and more efficient, the fundamental question arises: How can I migrate a substantial portion of data that functions as UI state but is actually retrievable from the server?

The State definition

State refers to any type of content that may not be retrievable from a remote server or data that will be lost if the application unexpectedly terminates. It can be stored locally, either in a local storage or in memory. The responsibility of managing this data lies with the developer, and typically, the server is unaware of its existence or simply does not concern itself with it at the moment.

Although it may initially appear complex and abstract, particularly in the context of frontend development, the design of your data flow on the client-side can be simplified. In most cases, you will only have temporary component-level input data, such as color themes or platform-specific user preferences.

For instance, consider a payment information form. Before sending the processed data to the server, each stage of the data is stored in the state. This means that if the user closes the browser (assuming it’s a web application), the data will be lost. The server only considers the final input; it is not concerned with the temporary text within each input. The focus is solely on the data snapshot that is sent to the server.

The Cache definition

Data in this context refers to information obtained from API responses that can be easily retrieved again without significant effort. This data can originate from a remote web server or a local database. Notably, the responsibility for handling the storage of this data lies outside your purview.

For example, within a REST API, you may have the ability to input additional data. However, it is not your responsibility to manage this data; therefore, all data calls from the API should be stored in a cache.

That’s nothing new!

You might be thinking, “That’s nothing new! Libraries like swr and react-query have been handling this in the React world for years!”. And you are absolutely correct.

These libraries do a great job at abstracting remote data and creating a self-managed cache, eliminating the need for manual management. If you were to handle it yourself, you would likely end up “statizating” your cache once again.

At this point, you could choose to stop reading this article and begin noticing how various applications use state to store remote data, even recognizing it as a poor practice. You might even consider migrating to a modern client and storage solution like swr or react-query.

Just a few more things

When APIs are developed to serve third-party applications, such as the Telegram API that caters to multiple clients, they often adopt a “cache first” approach. Caching becomes crucial in order to scale data transfer rates and reduce bandwidth usage, making it an excellent helper in such cases (Although you may want to read about server-side caching).

On the other hand, if you are building a frontend for a “closed API” or “closed product,” where the backend only serves their own frontend, caching may not be a top priority. In this scenario, if caching is implemented at all, it is typically integrated into the frontend API client and not a mandatory requirement.

This is a very common scenario and it’s not bad, but it’s important to be aware that both scenarios require different approaches to cache management. With this logic, APIs in general prefer to bypass the server tier and implement a single tier cache. Which ends up resulting in two isolated caching layers, possibly one on the server with all its custom logic and a simpler one on the client, like using just TTL.

These are super generic and easy approaches, but when you’re interacting with a cache first API, using a integrated cache layer (which mimics caching behaviors that the last layer calculated, such as when an HTTP server returns a cache-control header) should also be one of the considerations, as it will represent the most accurate data for that moment and context. This can lead to a data inconsistency if your remote server was built with the mindset to be something like I described earlier as a closed API.